Preparations and work on the project have been such a big part of our work over the past few months that it’s a bit overwhelming to realize how far along we’ve come. And, of course, there’s the immediate pressure of making sure we get everything exactly right. The general fear that many experience when they realize they might have included a typo in a blog post or press release is nothing compared with the fear that you’ve made a mistake on a monumental bronze sculpture that will exist and be seen by millions of people for perpetuity.

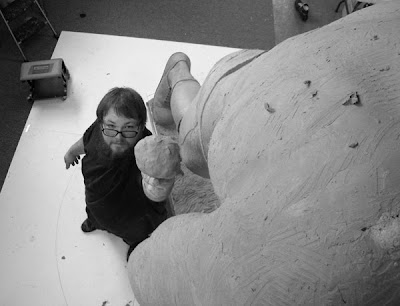

To the outside observer the sculpture seems all, but finished. Crow nearly sprints off his clay grass. Equipped in his period appropriate uniform, the sculpture features everything from detailed spikes on his cleats to the unique stripping found on mouth guards of that era. And yet, there is still much to do before the sculpture can be deemed, “finished.” I know from experience that it’s this final stage that Steven finds the most challenging. His current work days don’t have the immediate gratification of the early stages of the project. He can’t leave for the day content that there is an arm or leg that wasn’t there before. Instead, it’s a constant processes of evaluating and perfecting - checking on the draping and seams of the uniform and making sure that the texture of the piece is cohesive and suggests the different materials and finishes at play on the figure. It’s a difficult balance between making sure every detail is correct and preventing the sculpture from looking over-worked.

It’s the kind of details that only Steven and John David himself can see. For this reason we were thrilled when John David called late this week to say that he would fly in from Texas to give final notes on the project. It’s clear that in the time between today and his first visit early this fall he has come to terms with the project and accepted both the honor and the responsibility of the recognition. He came to the studio with a small leather (maroon of course) notebook with the list of questions and suggestions that he and his wife Caroline had compiled.